How Airlines Safely Dispatch Aircraft With Failed Equipment (the MEL)

Every day, airlines dispatch aircraft with broken equipment. Legally. Safely. Routinely.

If you’re a software engineer, your first instinct might be horror. They’re flying passengers with known defects? But here’s the thing: aviation’s approach to handling failures is remarkably sophisticated, and there’s a lot we can learn from it.

I’m an airline pilot who started out as a software engineer. Let me introduce you to the MEL — the Minimum Equipment List — aviation’s elegant solution to a problem every software system faces: what do you do when something breaks?

The Problem: Perfect Systems Don’t Exist

A modern airliner has millions of parts. Some of these will fail. Not might fail — will fail. The question isn’t whether you’ll have failures — it’s how you handle them when they occur.

The naive approach would be: if anything breaks, ground the aircraft until it’s fixed. This sounds safe, but it introduces a host of other problems:

- It’s economically devastating: Aircraft cost tens or hundreds of millions of pounds. They need to fly to generate revenue.

- It creates perverse incentives: Pressure to “find” that something isn’t really broken.

- It ignores redundancy: Most systems are designed with backups. Grounding for a failed backup may be wasteful.

- It conflates criticality: A broken coffee maker isn’t the same as a broken engine.

Sound familiar? This is exactly the problem we face in software when deciding whether to roll back a deployment, disable a feature, or wake someone up at 3 AM.

Enter the MEL: A Pre-Computed Decision Tree

The Minimum Equipment List is a document that explicitly defines what equipment can be inoperative for dispatch (i.e., still legally go flying), under what conditions, and for how long.

Here’s a simplified example from an A320 MEL:

| Item | Number Required | Number Installed | Category (Repair Interval) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weather Radar | 0 | 2 | C (10 days) | Day VMC (visual meteorological conditions — clear blue skies!) only. Avoid known precipitation. |

| Engine Fire Detection Loops | 1 per engine | 2 per engine | A (1 flight) | Max 3 days |

| Coffee Maker | 0 | 3 | C (120 days) | — |

| Transponder | 0 | 2 | B (3 days) | May not operate in certain airspace (NAT — North Atlantic Tracks) |

If you’re interested, the entire A320 MEL is publicly available online from the FAA website. Scroll to a random page and see what is allowed to be broken — and what the implications and restrictions are.

You’ll also notice that each item has an ID in the form xx-xx-xx, which corresponds to the aircraft’s maintenance manual and our pilot-oriented “Flight Crew Operating Manual”. This allows for easy cross-referencing between the MEL and the detailed technical documentation for each system.

For example, 21-52-01 indexes to “Air Conditioning System - A/C Packs - One Pack Inop”. The first “21” refers to the ATA number for the associated system, which is shared across manufacturers. Neat!

The MEL isn’t something an airline just dreams up. It’s derived from a Master MEL published by the aircraft manufacturer and approved by aviation authorities — and airlines can only make it more restrictive, never less.

Aside: The CDL

There is a second, complementary document called the CDL — Configuration Deviation List. The CDL deals with non-structural external aircraft parts that may be missing with the aircraft still being safe to fly. For example, a missing piece of the rubber seal around the landing gear door might be listed in the CDL with specific conditions for flight.

There is often a fuel-burn penalty or performance penalty (which must be accounted for when calculating our take-off power setting and speeds).

The MEL as a Feature Flag System

If you squint, the MEL is essentially a feature-flag system, with:

- Explicit degradation modes: Not just on/off, but “on with restrictions”

- Time-boxed exceptions: Items have defined repair intervals (24 hours, 3 days, 10 days, 120 days)

- Compensating procedures: Shown in the MEL with an (O) meaning “operational procedure” — specific steps the flight crew must carry out differently when equipment is inoperative

- Combinatorial logic: Item X being inoperative might prohibit Item Y from also being inoperative

In software terms: imagine a flag that doesn’t just disable recommendations, but flips the whole site into a “degraded mode” — static best-sellers, no personalisation, no background jobs — plus a hard expiry date and a runbook that says exactly what humans need to do differently until it’s fixed.

Lessons for Software Engineering

0. Risk

Aviation, like much of life, relies on a careful balance of risk. If we were all 100% risk-free, we would never leave our house, and certainly wouldn’t go flying!

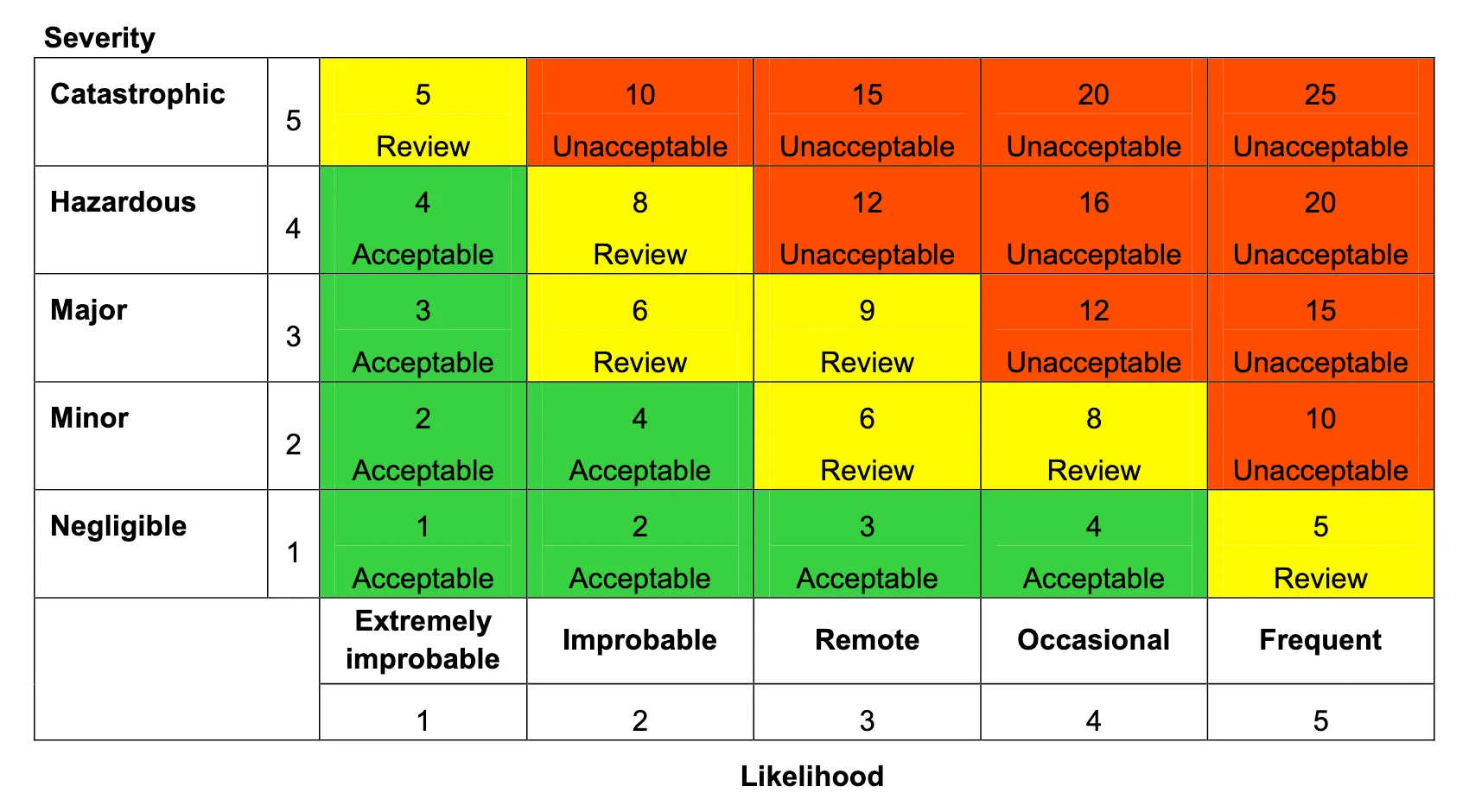

The basic formula for risk is risk = probability × severity.

This might seem obvious: even if the risk of failure is near-zero, if the severity is life-threatening then the system needs additional redundancy and/or careful consideration!

In software: Think about the severity of a system failing, and balance that with the amount of redundancy needed for that system. Your primary database: critical. Your email-sending queue: it can be down for a few minutes unless it’s mission-critical.

1. Pre-Compute Your Failure Modes

The MEL exists before failures occur. Engineers and regulators have already analysed every system and determined:

- Can the aircraft safely operate without it?

- What restrictions apply?

- How long can we defer repair?

In software: Don’t wait for an outage to decide what’s critical. Document your system’s failure modes in advance. What happens if your cache layer is down? If the payment provider is slow? If product recommendations are unavailable?

2. Distinguish Between “Broken” and “Unacceptable”

Not all failures are equal. Aviation explicitly categorises equipment:

- Required for flight: No exceptions (flight controls, engines)

- Required by regulation: Depends on airspace, conditions

- Required for passenger comfort: Deferrable

- Redundant systems: One can fail if backup works

In software: Your feature flag system should distinguish between:

- Core functionality: If authentication is down, the whole system is down

- Degraded but usable: Product search is slow but works

- Nice-to-have: Personalised recommendations are unavailable, users survive

3. Time-Box Your Technical Debt

MEL items have repair intervals. You can’t fly forever with a deferred defect, even just the coffee brewer. The categories (A, B, C, D) create forcing functions:

- Category A: Specified time (often 24 hours)

- Category B: 3 calendar days

- Category C: 10 calendar days

- Category D: 120 calendar days

In software: When you ship with a known bug or workaround, set a deadline. Put it in the sprint. Add a calendar reminder. The MEL philosophy: deferral is acceptable, indefinite deferral is not.

4. Document Compensating Procedures

When a system is degraded, the MEL often requires carefully designed “operational procedures” — things the flight crew must do differently. For example:

Weather Radar Inoperative: Avoid areas of known precipitation. Do not dispatch if thunderstorms are forecast en route. Daytime flight only

In software: When a feature is flagged off or degraded, document what changes:

- Does the support team need different scripts?

- Should error messages change?

- Are there manual processes that need to activate?

5. Consider Failure Combos

When one redundant system fails, will this put greater strain or importance on a complementary system remaining healthy? If so, we should carefully map and consider system interdependencies to prevent unexpectedly eroding safety margins further than intended.

For example, two seemingly unrelated systems — the air conditioning system and the spoiler (speed brake) system — are risk-linked in a hidden way.

If operating with 1 of 2 air conditioning systems failed per the MEL — which is allowed — then the spoiler system must be fully functional. In the event of the other air conditioning system failing, the aircraft would need to perform a rapid descent to maintain a safe cabin pressure, and the spoilers greatly contribute to our descent rate during such a procedure.

Independently, it is acceptable for a single pair of spoilers to be inoperative per the MEL, but it can’t be combined with any air conditioning failure. (See page 49 in the A320 MEL linked above for the full details.)

In software: Consider the interconnectedness of your systems. If your DNS server falls over, will this take out everything else? Can systems be designed in such a way that their redundancy doesn’t degrade when another system fails?

6. The Power of “No”

Some things simply cannot be inoperative. The MEL explicitly lists what’s required for safe flight. There’s no negotiating with physics.

In software: Have the courage to define what cannot be compromised. What’s your “cannot dispatch” list?

- Authentication

- Data integrity

- Audit logging

- Rate limiting on critical endpoints

The Cultural Lesson

The most profound thing about the MEL isn’t technical — it’s cultural.

Aviation created a system where pilots, crew, and engineers are expected and required to identify and report equipment failures. There’s no shame in flying an aircraft with MEL items. The paperwork exists, the procedures are defined, and everyone knows how to operate safely in degraded conditions.

Compare this to many software organizations where:

- Bugs are hidden because they reflect poorly on someone

- Technical debt is invisible to leadership

- “It’s fine, it’s been broken for months” is somehow acceptable

- There’s no defined process for operating with known issues

The MEL normalizes imperfection while demanding accountability. Yes, this is broken. Yes, we can still operate. Yes, we will fix it by this date. Yes, we’re tracking it.

Closing Thoughts

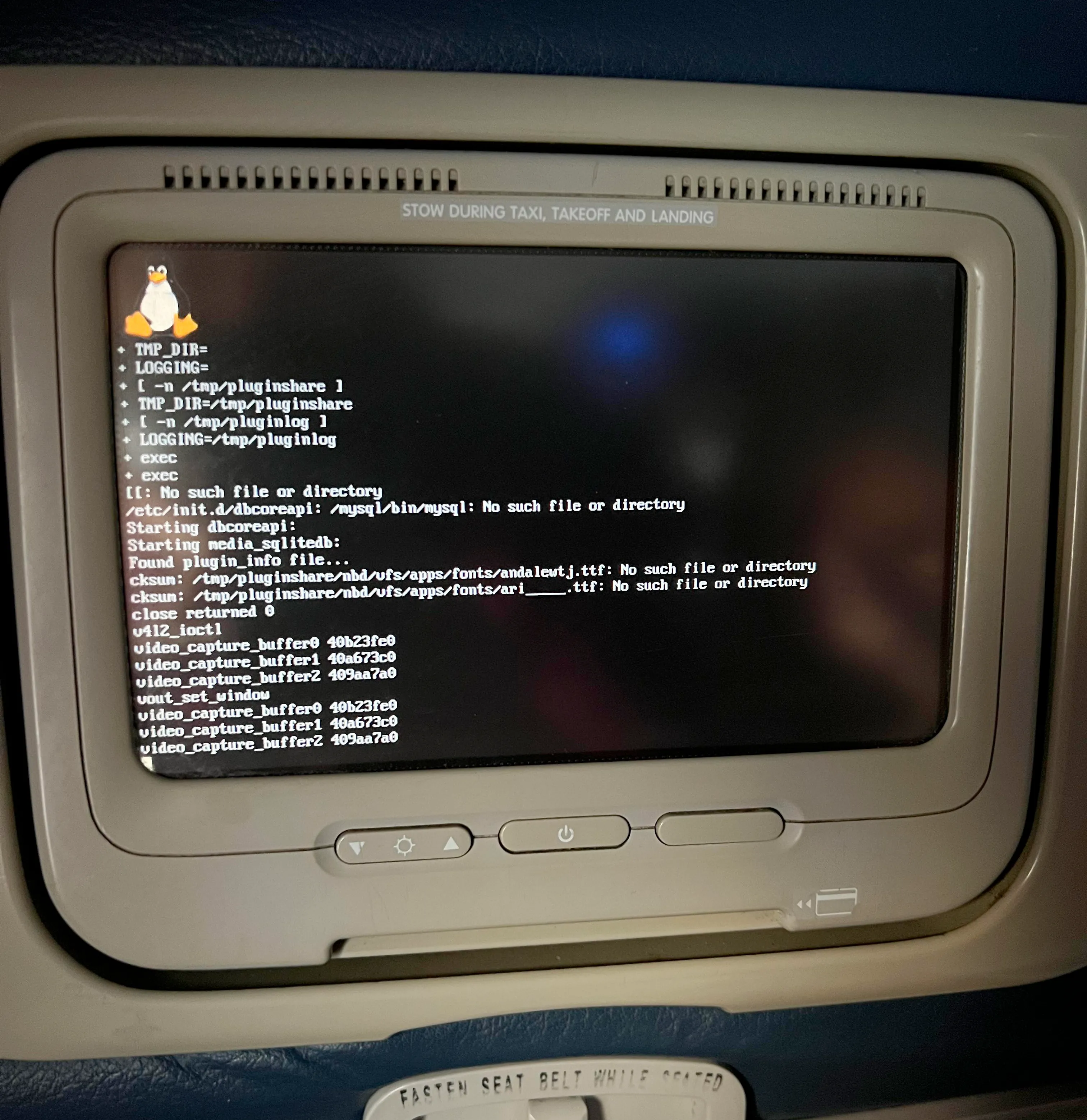

Next time you’re on a flight and the entertainment system isn’t working, or the captain announces “we’re waiting for a quick maintenance item” — you might be witnessing the MEL in action.

It’s not a sign of poor maintenance or cutting corners. It’s evidence of a mature system that has thoughtfully pre-computed its failure modes, explicitly documented what’s acceptable, and created clear accountability for returning to full operation.

That’s not just good aviation. That’s good engineering.

I’m an airline pilot flying the Airbus A350. I also write code. If you enjoyed this intersection of aviation and software, you might like my posts on querying my pilot logbook with SQL or the interactive visualizations of my flight data.